Flying over objects at constant height

Published:

Ever since I got the Crazyflie and learned about Kalman filters at Udacity, I’ve been wondering about how to make a drone fly at constant height – defined as altitude or above sea level height.

The problem

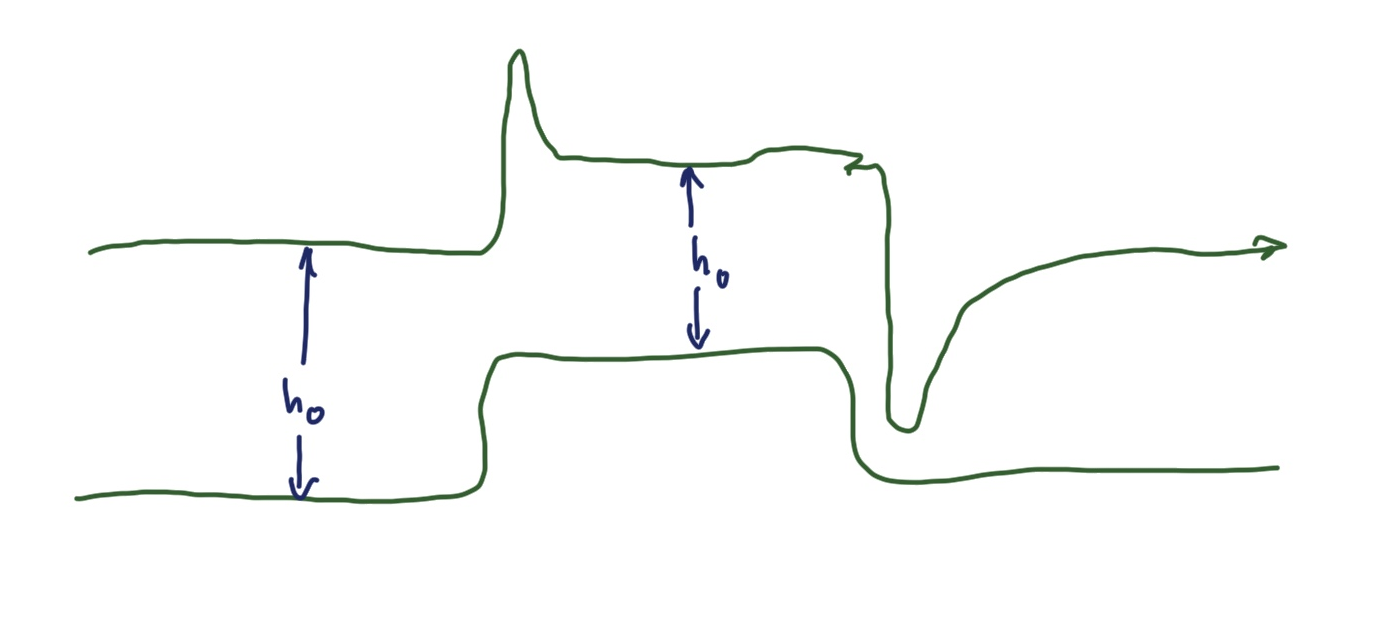

With the state estimator and the controller of the stock firmware, the crazyflie jumps up and down like crazy whenever it encounters something underneath its flight path, overshooting when the obstacle is coming, undershooting when the obstacle is just behind it.

In the process, it often loses control crashing. Why?

The way I understand Kalman filters is the following:

- we start with some state estimate $\hat x_t$

- given some control input $c_t$ we predict the next state $x^{pred}_{t+1}(x_t, c_t)$

- the control input is chosen such that we get close(r) to a given goal state or setpoint $x_{set}$.

- we update the state estimate for time $t+1$ using current sensor input $s_t$, so we get $\hat x_{t+1}(s_t, x^{pred}_{t+1}(x_t,c_t))$

and then we repeat the process.

What is the behavior I’d be interested in?

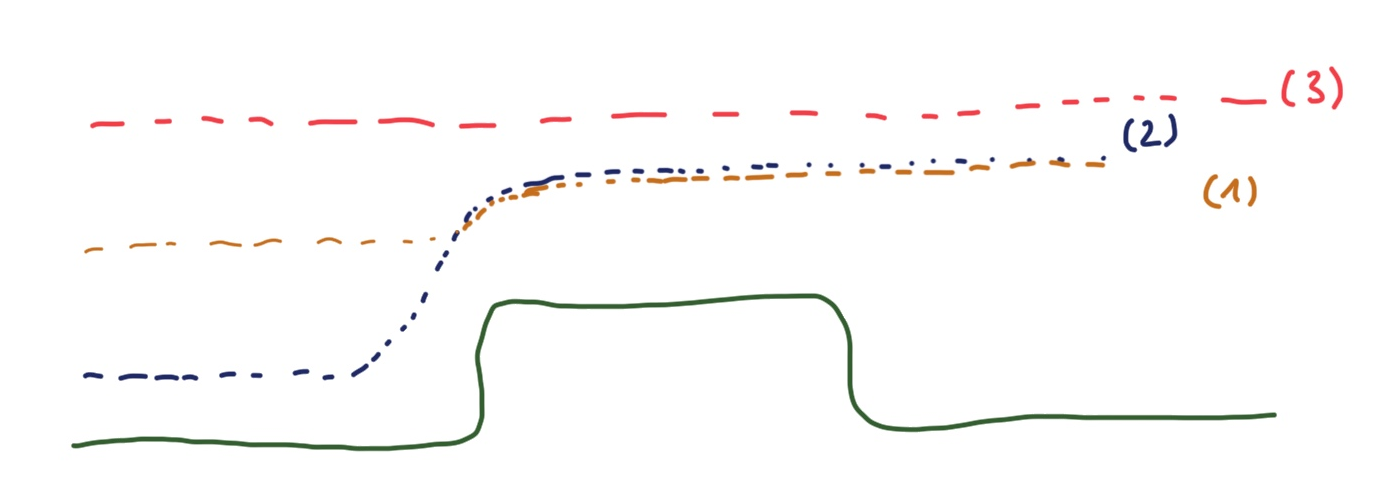

- fly at constant altitude as long as there is no indication of altitude loss or you fall below the minimum distance $d_{min}$ to the object [3]

- when approaching the obstacle with height $h_{obs}$, and you’re below the edge, smoothly fly upwards until you reach some minimum height $d_{min}$ between the obstacle surface and the crazyflie [2]

- when coming towards the obstacle at a height between $(h_{obs}, h_{obs}+d_{min})$, smoothly fly upwards until you reach altitude $h_{obs}+d_{min}$ [1].

Note that $d_{min}$ is defined as a minimum distance between drone and surface; we don’t want to get too close to any surface around us.

$d_{min}$ is what is sensed by the flow deck; altitude can be measured by the barometer. We want to fly at constant altitude as long as we keep a minimum distance to the surface below.

Expectations matter

If you were flying the drone yourself, you would see the obstacle coming and adjust your flight path to smoothly go up and over the obstacle. We could achieve this with the multiranger deck if we are in situation [2], but not in situation [1] or [3]. In those, only image processing or distance measurements in more directions (sonar, lidar-like) would give input that something is in the way.

Only if we perceive what’s coming can we adapt early and smoothen our flight path (and hence avoid overshoot).

Ignoring measurements and adapting control intent

What about situation [3]? In this situation a sensor detects a change in the environment that we as designers believe does not necessitate a reaction by the controller. Intuitively, we’d rather adapt our control setpoint $x_{set}$ based on our ‘problem assessment’ of the sensor reading than to adjust the flight path.

Likelihood based on previous state

How likely is it that I am where I measure to be now given my last state? One reaction to an ‘outlier’ measurement of my state (i.e. the flow deck saying I just lost 60% of height one instant) would be to compare to the previous state and say: can’t be, too unlikely. And then just ignore that measurement, and adapt my setpoint.

But this may lead to a loss of agility of the drone: too many new states would have to be deemed outside the ‘bounding-box’ of likelihood. It might have an averaging effect.

Likelihood based on previous control input

So a better way would be to ask: how likely is it that I am where I measure to be given my last state $x_{t-1}$ and control input $c_{t-1}$? To judge this, I have to develop a model of my controller that yields a probability distribution $p$ of new states $p(x\rvert c)$ given controls $c$ and then decide when to discard a measurement for control (and use it instead to update my setpoint $x_{set}$), and when to use the measurement in the state estimator and hence for control.

In some sense discarding the measured value can also be understood as being part of the sensor model, the way the flow deck works: it’s simply not a good guide when trying to fly at constant altitude over obstacles. What’s new is that we use the measurement to update our desired state, so we can continue to use the sensor for something useful (i.e. state estimation).

Can we use the barometer to decide?

Is there anything else that should shape our distribution $p(x \rvert c)$? Well we could try to use the barometer data. The problem is that the barometer is very sluggish and imprecise, and the flow deck laser range sensor is very fast and precise – so our decision would be based on really the worst data available.